Heraldry [/’hɛrəldri/]

noun, plural her·ald·ries

the science of armorial bearings.

the art of blazoning armorial bearings, of settling the rights of persons to bear arms or to use certain bearings, of tracing and recording genealogies, of recording honors, and of deciding questions of precedence.

a heraldic device, or a collection of such devices.

a coat of arms; armorial bearings.

heraldic symbolism.

Heraldry is the study of a coat of arms (also known as armorial bearings),like how sociology is the study of society or how kinesiology is the study of human movement. A coat of arms is a coloured (or lack of) symbol that belongs to an individual, office, or an organization. Each colour and symbol within a coat of arms has meaning, purpose, or history associated with that individual, office, or organization. This collective set of symbols becomes an identifier and extension of the owner (also known as armiger) during their lifetime.

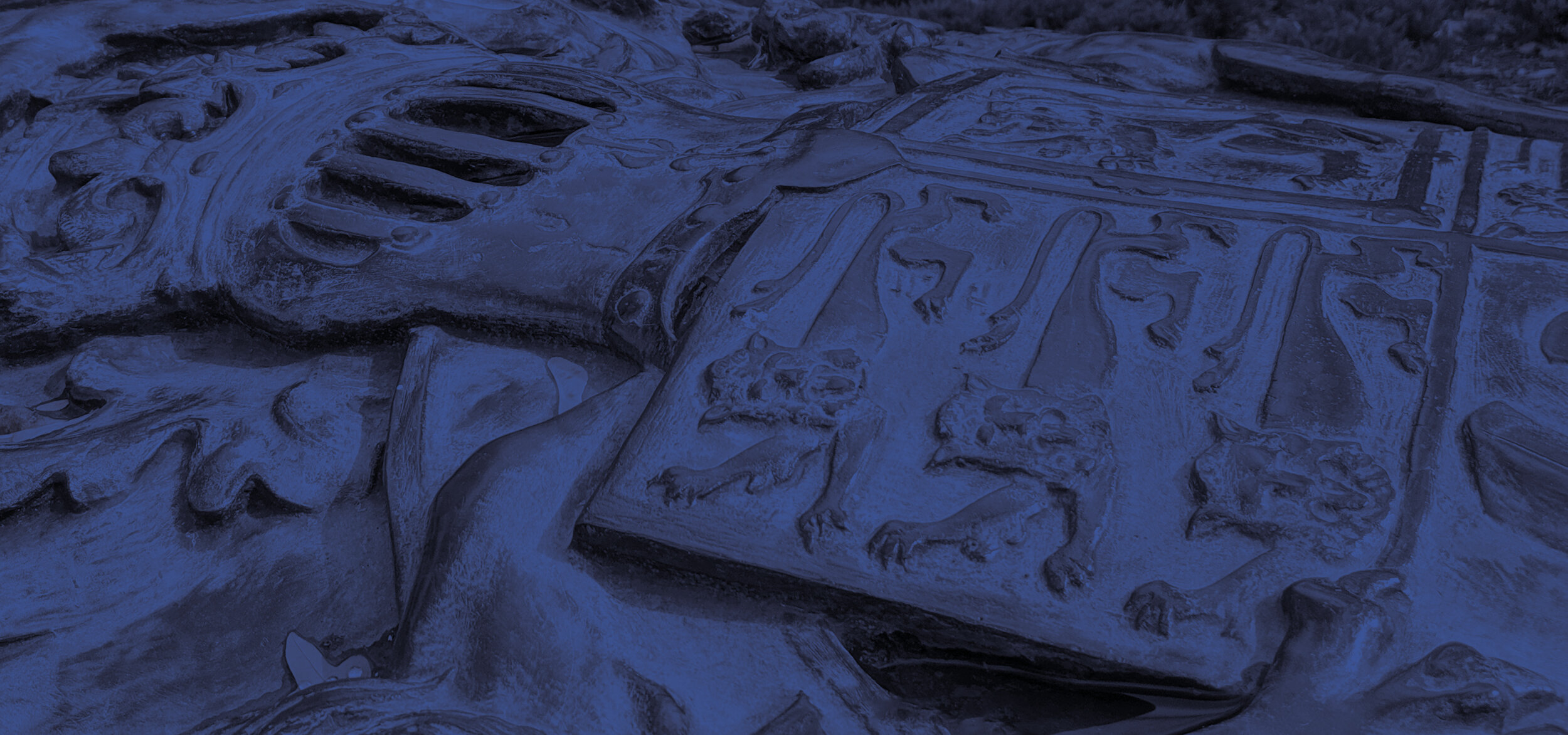

Soldiers at the Battle of Aljubarrota, 1385 (Jehan de Wavrin, Recueil des croniques d’Engleterre, 1470-1480)

Brief History of Heraldry

Heraldry has a confusing history. While the development and history of how heraldry came to be varied between heralds, historian, and regions, one thing is clear: that heraldry was invented during the Middle Ages (Bradbury, 2004). This medieval invention functioned as a form of identifying individuals and armies on the battlefield through specific shield decorations. While heraldry was initially a military development to identify an individual, the practice grew to involve families and corporate bodies.

The Battle of Crécy (Jean Froissart, Chronicles, 1322-1400)

The Harding Bible (Dijon, Biblioteque Municipale 14) is a manuscript dated 1109-1111 from the Abbey of Cîteaux, a Cistercian abbey, notable for being the original house of the Cistercian order. Figure 1 denotes a depiction from this manuscript made by Stephan Harding, a Cistercian monk (Born 1050 – Died 1134), which supports the claim that coat of arms was developed in the 12th century. While the illustrations seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2 are of biblical figures, they appear to follow the heraldic rules of composition.

Figure 2. Various depictions of an enamel effigy of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou (Le Mans, France)

One prominent claim of the earliest documented heraldry was that of Henry I of England, where he knighted his son-in-law Geoffrey (Born 1113 – Died 1151) – granting him the use of gold lions in 1128 (Woodcock & Robinson, 1988). Empress Matilda of England (Born 1102 – Died 1167), Geoffrey V’s wife, commissioned an enamel effigy for his tomb, which depicts a shield of gold lions on a blue field (see Figure 2).The contentious piece of history here is that these accounts were written well after Geoffrey V’s death and that the practice of creating funerary plaques was created 1155-1160 (Pastoureau, 1997).

The term ‘Herald’ was reserved for individuals who made announcements for a sovereign or sent a message on their behalf (Bradbury, 2004).Due to the nature of their role of being a messenger, they often accompanied royalty and were involved in military affairs. This diplomatic function of Heralds was what made them vital to the sovereign and state they served. In addition to exchanging information and communicating with an opposing force or a neighbouring sovereign, Heralds made announcements in tournaments – a historic announcer.

Figure 3. German knight, Hartmann von Aue (Minnesänger, Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift, 1304)

As a result of the developments of armour in the 12th and 13thcentury, the bearer became less visible. It became difficult, if not impossible, to identify the individuals beneath the helmets. Whether the bearer wore armour for battles or tournaments, they had their arms (or armorials) painted on their shield, helmet, or coat. This made it easy for the audience, the opposing force, or their allies to distinguish their identity (see Figure 3). A Herald’s role during tournaments included identifying these bearers of arms. As well as registering participants, enforcing regulations, and describing, as well as regulating the arms of those in the tournament (Bradbury, 2004).

Figure 4. Letters Patent Authorizing the Granting of Armorial Bearings in Canada

Throughout the centuries after the Middle Ages, Heralds became the sole regulators and supervisors of Coat of Arms and were the subject matter experts in adjudicating cases of dispute. In Europe, Heralds formed colleges and founded libraries. In Canada, the Heralds are officers in the Canadian Heraldic Authority, appointed by the Governor General. It was through the commitment and consistent of our Society that the Canadian Heraldic Authority was born through the Letters Patent (see Figure 4) from the Queen in 1988.

Armorial Bearings, what are they?

Armorial Bearings, most commonly known as a Coat of Arms, are the symbols or design depicted on a shield (men or corporation) or lozenge (women). In Canada, armorial bearings are granted by the Crown, through our Governor General. More specifically, this service is provided by the Canadian Heraldic Authority (CHA), whose role is to, “create coats of arms, flags and badges” (2020). Individuals or corporations who are entitled to armorial bearings are also known as armigers.

Figure 5. Arms of the Canadian Heraldic Authority (1994, Vol. II, p. 281)

Parts of a Grant of Armorial Bearings

The combination of the shield and crest is also known as the heraldic achievement, or just simply the coat of arms or armorial bearings. The armorial bearings consist of various parts. Please note that the descriptions below detail traditional practices, and that there is likely an achievement that does not meet these guidelines as there have been exceptions, altercations, and assumptions in the history of heraldry.

Figure 6. Arms of the Corporation of the City of Guelph, Ontario (1993, Vol. II, p. 133), originally recorded with the College of Arms, London, England, on 8 May 1978.

Blazon

The formal description of a coat of arms is known as blazon. This is often a combination of English, Norman French, and Latin. A blazon uses little to no punctuation, and applies a simple structure where adjectives follow the nouns they are describing. A blazon is provided for each part of the armorial bearings.

The blazon for Guelph’s full heraldic display is as follows:

Arms (Shield)

Argent on a fess Gules cotised Vert between three ancient crowns Gules a horse courant Argent;

Crest

Within an ancient crown Gules a mount Vert thereon a lion statant Or anciently crowned Gules resting the dexter forepaw upon the haft of an axe head downwards and inwards proper;

Supporters

Upon a grassy mount with on the dexter side in front of a copse a felled tree trunk lying to the dexter in the stock an axe proper in front of the same a man with a hat open shirted in breeches and boots proper vested of a tail coat cut away Gules sinister a female figure proper vested Argent cloaked Azure wearing a helmet Or crested Gules supporting with her dexter arm a trident points upward Sable and holding by the sinister hand a cornucopia proper;

Figure 7. Crest of Guelph’s Heraldic Achievement

Crest

The crest is an ornament mounted on a helmet. This originated from the decorative sculptures worn by knights in tournaments.

Figure 8. Crown (Ancient Crown) of Guelph’s Heraldic Achievement

Coronet

A coronet, crown, chapeau, eastern crown, the naval crown, loyalist coronet (civil & military), or a mural coronet is found above a wreath. If there is no wreath, then it is placed immediately above the shield. Coronets indicate rank or serves as a symbolic representation to the armiger and is part of the crest.

Figure 9. Wreath of Guelph’s Heraldic Achievement

Wreath

The wreath, also known as a torse, is a twisted strand with six folds. It is placed immediately above a helmet or the shield and it alternates between two tinctures (metal and colour) from the whole achievement. The first fold beginning from the dexter side (viewer’s left) is always a metal tincture.

Figure 10. Helmet of Guelph’s Heraldic Achievement

Helmet

In Canada, helmets do not serve a function and it is not blazoned. It can be found in a range of styles.

Figure 11. Mantle of Guelph’s Heraldic Achievement

Mantling

The mantling (or a mantle) is a small cloak that hangs down the back of the helmet. Its original purpose was to protect the wearer from the sun. In contemporary heraldry, it is used as a decorative accessory found on the dexter (viewer’s left) and sinister (viewer’s right) of the crest and shield. Like the wreath, it displays the two primary tinctures (metal and colour) from the whole achievement. Traditional practice with mantling is thatthe outside is the colour, whereas the lining is the metal. The mantling is not blazoned.

Figure 12. Arms (shield) of Guelph’s Heraldic Achievement

Shield

This is the most important element of a heraldic achievement. It is the part of the achievement that depicts the armorial bearings of the armiger. The shield comes in various shapes. However, if the armorial bearings are depicted on a lozenge, it denotes that the bearer is an unmarried woman or a widow.

Figure 13. Supporters of Guelph’s Heraldic Achievement

Supporters

Supporters are real or imagined figures that appear on the dexter (viewer’s left) and sinister (viewer’s right) of the shield to hold it up.

Figure 14. Compartment of Guelph’s Heraldic Achievement

Compartment

A compartment is a design placed under the shield and serves as a landscape that supporters are placed upon. Compartments complement the arms and is therefore consistent with the design of heraldic achievement.

Figure 15. Motto of Guelph’s Heraldic Achievement

Motto

The use of a motto likely developed from medieval war cries. An armiger’s motto often consists of a word or phrase expressing sentiment, virtue, or a pun on the bearer’s name. It is usually placed beneath the shield and supporters but could be placed above the shield as well. Mottoes can use any language, often English or Latin.

Guelph's Heraldic Achievement

Figure 16. Full heraldic achievement of the Corporation of the City of Guelph.

In preparation for Guelph’s proclamation as a city on April 23, 1879, the Town Council adopted a coat of arms. On the left side was an axeman standing beside a tree stump, representing John Galt’s ceremonial felling of a mighty tree to create Guelph. On the right side, Britannia, with gown, helmet and shield, represented Guelph’s links with the United Kingdom. She held a cornucopia containing the bounty of the rich soil of Guelph. In the centre, as Guelph’s arms, was a shield with the symbolic white running horse of Hanover, the ancient principality in Germany where the Guelph royal connections go back 1,000 years. On top was the supposed Guelphic crown with a lion on it.

While the coat of arms was used extensively, it was unofficial / assumed. In 1977, to commemorate Guelph’s 150th anniversary, the City decided to redesign and register Guelph’s crest with the College of Arms in London, England. A well-known artist, Eric Barth, assisted by a panel of local historians, updated the coat of arms and corrected heraldic and historic errors. It was approved and made official in 1978 (About Guelph, 2020).

How to Obtain Armorial Bearings

In Canada, the Canadian Heraldic Authority (CHA) is responsible for creating coats of arms, flags, and badges. The CHA was created in 1988 and is headed by the Governor General, who appoints its officers, called heralds.

In Canada, the CHA manages the official creation of coats of arms, flags and badges. All Canadian citizens and organizations (municipalities, schools, associations, etc.) can contact the Chief Herald of Canada to have heraldic emblems created for them. A grant of armorial bearings is an honour conferred within the Canadian Honours System in recognition of service to the community (Citation). Please note that the costs associated with a grant of armorial bearings is the petitioner’s responsibility, and not at the public’s expense.

Letters Patent granting Armorial Bearings to The Royal Heraldry Society of Canada

Why is Heraldry important?

Heraldry is one of the oldest methods and art forms of distinguishing individuals and families. It was developed in the Middle Ages before surnames were used and long before literacy was accessible to the masses. During the Middle Ages, the use of coats of arms was exclusive to high nobility. Today, a grant of armorial bearing can be petitioned for by an individual or a corporation in recognition of service to their / our community.

Today, heraldry is important because it is a preservation of historical art practice and a method of understanding one’s family history (genealogy). Most importantly, heraldry serves as a contemporary form of storytelling. The symbols (devices) used in a heraldic achievement provides contexts of unions, values, profession, and passion of an individual, their family, or a corporation.

To learn more about heraldry, we encourage you to register for the Society’s Heraldry Proficiency Program.

If you’re interested in heraldry, you may also be interested in vexillology (study of the history, symbolism, and use of flags) and genealogy (the study of families, family history, and ancestral lineages).

What Can You Do With Your Armorial Bearings?

Your heraldic achievement is more than parchment, it's an extension of who you are! For example, you can have it made into a seal, bookplate, stained glass, flag, banner, stationaries, and blazer badge, as well as silverware and cookware.

References

Ailes, A. (1982). The origins of the royal arms of England. Reading, England: Graduate Center for Medieval Studies, University of Reading.

Bradbury, J. (2004). The Routledge companion to medieval warfare. New York, New York: Routledge.

Pastoureau, M. (1997). Heraldry: Its origins and meaning (Garvie, F., trans.). London, England: Thames and Hudson/New Horizons.

Woodcock, T. & Robinson, J.M. (1988). The Oxford guide to heraldry. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.